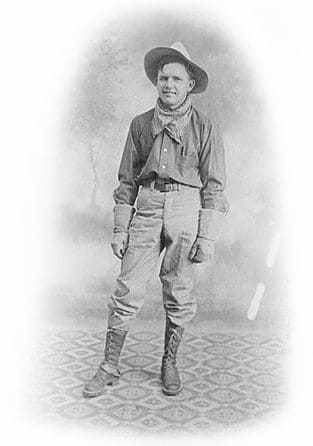

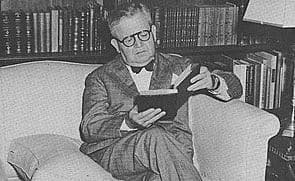

Everett Lee DeGolyer (1886-1956) attended the University of Oklahoma beginning in 1905, worked for the United States Geological Survey while attending college, later formed Amerada Oil Company, was the director of the American Petroleum Institute (API) for 20 years, founded the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG), created Core Lab and the world renown petroleum engineering firm of DeGolyer and MacNaughton. His development of reflective seismology ultimately led him to be called the “father of geophysics.” As an advisor to the United States government regarding reserve estimates and reserve categories, he was a staunch believer in reservoir pressure preservation, restricting well production for the sake of pressure preservation and conservation of America’s hydrocarbon resources.

Mr. DeGoyler’s accomplishments are too numerous to write about here, and I strongly recommend reading Oilfield Revolutionary, The Career of Everett Lee DeGolyer by Houston Faust Mount. It is a good read about a remarkable man in oil and gas history, perhaps one of the most important figures in our industry.

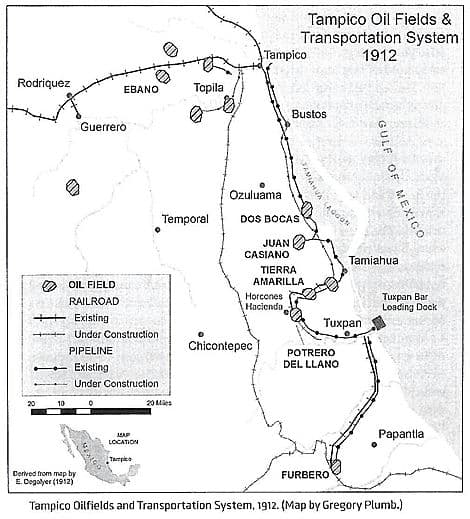

Mr Dee, as he was affectionately known later in his very philanthropic life, left the University of Oklahoma in his junior year (1909) and became a surface geologist for his old boss at the USGS, C. Willard Hayes, and the Mexican Eagle Oil Company, also known as El Aguila Oil Company. DeGoyler worked the area known as Faja de Oro, or the Golden Lane along the Eastern coast of Mexico, south of Tampico.

In the early 1900’s the jungles and coastal plains of Eastern Mexico were very remote and sparsely populated, the regions living conditions very difficult. Exploring early Mexican oil required extraordinarily tough men. The jungles were thick with no access other than by boat, or horseback, the heat and humidity unbearable and malaria and dysentery rampant. If that wasn’t enough, most of the Golden Lane of Mexico was developed during the very contentious Mexican Revolution (1910-1920) and the American occupation of Tamaulipas and the Battle of Veracruz in 1914.

To drill wells in that region of Mexico men hacked locations out of the thick jungle, barged cable tool rigs, pipe and cement up rivers and lagoons, then used mules and tractors to get equipment through swamps and bogs into remote places near surface highs and “chapapotes,’ or oil seeps. As minor discoveries were made along the Golden Lane trend railroads were eventually built inland, and pipelines were built toward the coastline to get oil out.

The history of early Mexican oil is fascinating, full of hard men with lofty visions, men like Edward Doheny of California (Huasteca Oil Co.) and Sir Weetman Pearson of England (El Aguila Oil Co.).

I highly recommend a number of reading sources on the subject of early Mexican oil. Few American’s realize, for instance, that the great conservative spokesperson, William F. Buckley’s, family had a significant presence in early Mexican oil history.

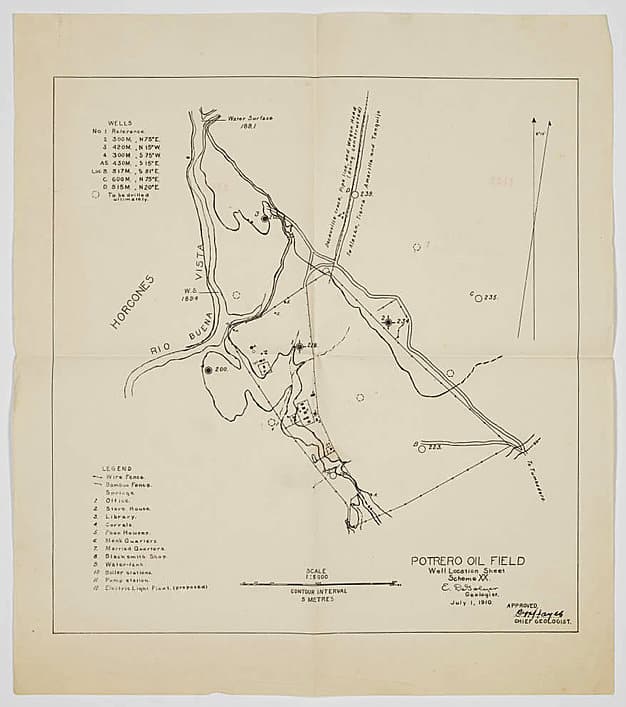

Everett DeGoyler’s geological focus was on El Aquila’s acreage position in the Tierra Amarilla area south of Ebano Field, discovered in 1901 by Ed Doheny. DeGoyler used a compass to determine the dip rate of rock outcrops at the foot of the Sierra Madres and projected them basinward, toward the Gulf of Mexico. Using a surveyors level and plane table he mapped surface anticlines several miles long, often with less than 20 feet of structural relief, in thick jungle.

After drilling two wells with good oil shows and one minor producer in a particular area of interest, DeGoyler picked the location for the Potrero de Llano No. 4 well, about 2000 feet WSW of the No. 1 well, seen below. He advised his bosses at El Aguila NOT to drill the well because of results from offsetting wells and $25,000 estimated D&C costs.

The Golden Lane of Mexico was home to many dry and “wet” wells drilled from 1901-1916, but it was also home to some of the most spectacular wells the world has ever known. Some eight miles south of the Potrero region, for instance, the biggest well in the world in terms of daily production rates (220K BOPD), the Cero Azul No. 4, was discovered in 1916 by Huasteca Oil.

El Aguila, Potrero de Llano Numero 4 was, however, a ‘warhorse of an oil well’. It is THE single most productive oil well in world history in terms of cumulative production.

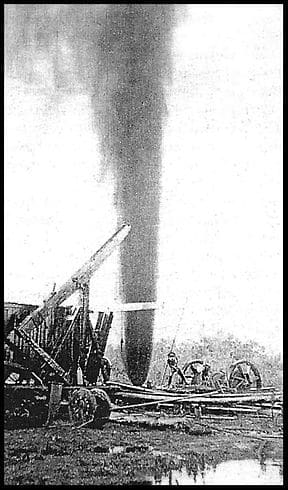

On December 27, 1910, Canadian drillers penetrated 50 feet of cavernous, Tamasopo limestone with cable tools at a TMD of 1,911 feet. There was no valve on the 8-inch casing when they started bailing at 02:00 hrs. in the morning. The well came in so fiercely it blew the bailer a mile away and all the rig into smithereens. Estimated initial flow rates down ditches to earthen dams and out into the nearby Buena Vista River was between 100,000 and 115,000 BOPD. The oil was 23 degrees API and very hot, estimated to be nearly 140 degrees. Estimated height of the uncontrolled flow was over 600 feet. Before the well was brought under control over two million barrels of oil was set on fire in the Buena Vista and Tuxpan River confluences to keep it from reaching the Gulf of Mexico.

It took two weeks to design and install a bell nipple with some sort of inverted slip segments on the bottom that could be “ratcheted “(DeGoyler) down over the 8-inch casing and a valve stabbed over the flow. Estimated SICP was 850 PSI. At shut in, the casing (set and cemented to 1,805 feet) started to lift out the ground. An 8-inch flowline was quickly installed straight to the bell nipple and connected to a pipeline that took the oil to Tuxpan, then north by tanker to El Aguila’s refinery in Tampico. The well flowed 39,000-43,000 BOPD for the next ten years, with no decline in FCP and no water. In early January 1920, the well completely watered out in a period of less than one month and was plugged. Its known total cumulative production was over 129 million barrels. Most of that oil was sold for less than 70 cents a barrel.

The well caught fire in 1914 from lightning and another 1.5 million BO was lost down the Tuxpan River, again, before the fire was extinguished and control regained. A giant cement cofferdam was built around the well and kept full of water to prevent additional fires from lightning strikes.

Well No. 4’s biggest operational expense, besides the marketing and transportation of its crude oil, was guarding it during the Mexican Revolution. It was surrounded in razor wire with guard towers and armed Mexicans on watch 24 hours a day for ten years.

Shortly after the No. 4 discovery, DeGoyler returned to Norman to finish his degree at OU. He returned to Mexico in 1911 and discovered Los Naranjos Field further to the south that ultimately produced over 100 million barrels of oil. Shallow (<2,000 feet) wells along the Golden Lane produced a total of 600 million barrels of oil from 1901 to 1919 and ultimately close to 2 billion barrels.

DeGoyler left the Golden Lane of Mexico in 1916 never to return. Pierson eventually sold El Aguila to Shell Oil in 1919. In 1938 Mexico nationalized its oil resources and all remaining oil production and associated infrastructure owned by foreign entities eventually became part of Pemex.

Mr De became severely ill in 1953 and had numerous prolonged stays in the hospital over the ensuing years. He killed himself in 1956. He was 70 years old.

The Everett DeGoyler Library at Southern Methodist University in Dallas contains all his personal journals, reports and maps of his work in Mexico.

(This post was originally published on June 26, 2018, by Mike Shellman)

https://www.oilystuffblog.com/single-post/2018/06/25/Mr-De-In-Mexico)